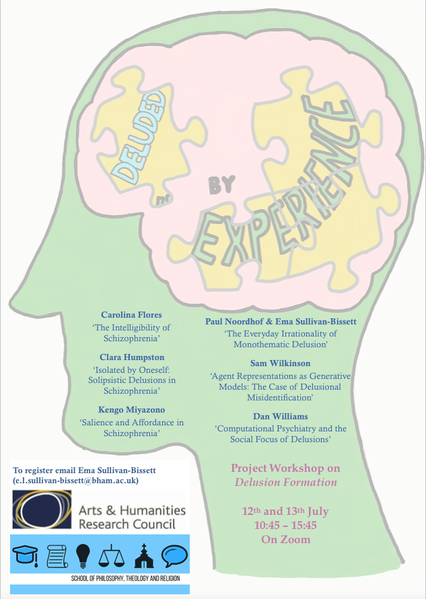

Project Workshop One: Delusion Formation

The first workshop of the project will be on delusion formation, featuring six talks from seven researchers in philosophy and psychology:

Carolina Flores (Philosophy, Rutgers)

Clara Humpston (Psychology, Birmingham)

Kengo Miyazono (Philosophy, Hokkaido)

Paul Noordhof (Philosophy, York)

Ema Sullivan-Bissett (Philosophy, Birmingham)

Sam Wilkinson (Philosophy, Exeter)

Dan Williams (Philosophy, Cambridge)

See below for the Programme and titles and abstracts. The workshop is free, open to all, and will take place over Zoom. For updates follow us on twitter @del_by_ex

To register email Ema: [email protected]

Programme

12th July

10:45-12:00: Kengo Miyazono: ‘Salience and Affordance in Schizophrenia’

12:00-13:00: Break

13:00-14:15: Sam Wilkinson: ‘Agent Representations as Generative Models: The Case of Delusional Misidentification’

14:15-14:30: Break

14:30-15:45: Carolina Flores: ‘The Intelligibility of Schizophrenia’

13th July

10:45-12:00: Paul Noordhof and Ema Sullivan-Bissett ‘The Everyday Irrationality of Monothematic Delusion’

12:00-13:00: Break

13:00-14:15: Clara Humpston: ‘Isolated by Oneself: Solipsistic Delusions in Schizophrenia’

14:15-14:30: Break

14:30-15:45: Dan Williams: ‘Computational Psychiatry and the Social Focus of Delusions’

Titles and abstracts

Carolina Flores: 'The Intelligibility of Schizophrenia'

People with schizophrenia are often thought to reason in unintelligible ways. For example, how are we to make sense of believing that one’s partner is unfaithful because the fifth-lamppost along on the left is unlit? In this paper, I draw on work on reasoning biases in schizophrenia (especially by Todd Woodward and collaborators) to argue that the reasoning patterns we find in schizophrenia are intelligible at the folk-psychological level. More specifically, I argue that the reasoning patterns characteristic of schizophrenia express an epistemic character—a unified set of epistemic values, preferences, and traits. For this reason, these patterns constitute an epistemic style and can be understood as expressing a distinctive way of being an epistemic agent. I offer an account of how this epistemic style contributes to the formation and maintenance of delusions in schizophrenia. This account suggests that schizophrenia is, at least in some respects, on a continuum with neuro-typical cognition. It entails that we should separate out intelligibility and rationality. And it helps us reframe questions of epistemic assessment in cases of schizophrenia.

Clara Humpston: 'Isolated by Oneself: Solipsistic Delusions in Schizophrenia'

If there is one concept which most individuals hold as absolute truth, it is likely that they, and only they, can access their thoughts, emotions and actions. Indeed, most people would not even question what makes a thought theirs in the first place – unless the person is mad (I refer here to the schizophrenic kind of madness specifically). Nothing seems to signal madness more than the claims that one is not the producer or owner of one’s own thoughts and actions; to most clinicians, it simply has to be a delusion that needs to be corrected with pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions.

I argue that the observations and interventions by the majority of well-meaning theorists and clinicians barely scratch the surface of the schizophrenic experience. It is extremely difficult to offer a deep enough understanding into what it is like to be on the receiving end of external interference coming from nowhere, or to hold the ‘belief’ that one is not the source or owner of thoughts present within one’s mental space. The core of the experience of a schizophrenic disorder in my view lies within this labyrinth of uncertain, paradoxical, unstable and unsustainable ‘in-between’ states of thought, perception and volition that in their totality contribute to what may be termed ‘ontologically impossible’ experiences sometimes leading to solipsistic delusions.

I aim to explain what it means to go through solipsistic delusions, their significance to the understanding of thought and perception, how they might help with the clinician’s differential diagnosis, before engaging in further discussion on ‘what if’ these experiences are not impossible after all. What if the unity of selfhood and its perceived links to first-personal givenness are nothing more than a historical or social trend? What implications will it have for the constitutive relationship between thinking and the existence of self that is taken for granted? My hope is that by contemplating such questions, theorists and clinicians alike will begin to grasp what it is like to be in the grip of the perplexity and paradoxicality intrinsically associated with schizophrenia, and to appreciate the patients’ realities and truths.

Kengo Miyazono: 'Salience and Affordance in Schizophrenia'

It is a popular view that delusions are (partly) caused by some altered experience. In schizophrenic delusions, the altered experience has something to do with abnormal “salience” (Kapur 2003). To say that an object X is “salient” is, roughly, to say that X “grabs” attention. My proposal in this paper is that X “grabs” attention if and only if X “affords” attention (McClelland 2020). Altered experience in schizophrenia thus involves some abnormal (mental) affordances. I defend this account of abnormal salience in schizophrenia from a recent objection by Ratcliffe and Broome (forthcoming) that both “salience” and “affordance” are unhelpful notions in understanding altered experiences in schizophrenia.

Paul Noordhof and Ema Sullivan-Bissett: 'The Everyday Irrationality of Monothematic Delusion'

Empiricist accounts of monothematic delusion formation have it that the anomalous experiences often had by subjects with these beliefs are explanatorily relevant to their formation. Many philosophers and psychologists have argued that in addition, there is some special irrationality involved in delusion formation, understood as the manifestation of some cognitive deficit, bias, or performance error. Key to this approach is the fact that not all people with anomalous experiences develop delusions, and so the thought goes that we can explain why some subjects develop delusions off the back of anomalous experiences while others do not by appeal to a special irrationality afflicting the former.

We argue that an examination of non-clinical paranormal beliefs shows that it is a mistake to think that monothematic delusional belief usually involves a kind of irrationality distinct from everyday kinds. We turn then to a question which naturally arises from the foregoing, if delusions are not the result of clinical irrationality, what are we to say about their status in this regard? We argue that although delusions are often seen as the most serious form of irrationality, they are in fact, in some ways, closer to the normal case than has been typically thought.

Sam Wilkinson: 'Agent Representations as Generative Models: The Case of Delusional Misidentification'

Social organisms don’t only perceive and reason about inanimate parts of the world; they also perceive and reason about other agents, namely, parts of the world that have in turn their own perspective on the world. What is this cognition (online or offline) of agents and how does it differ from cognition of inanimate parts of the world? My answer here is that agent cognition deploys agent representations, and that these representations are to be thought of as dynamic predictive models (DPM). One area where this account is especially illuminating is in our understanding of delusional misidentification. I end with some general lessons for how we are to think of social cognition more generally.

Dan Williams: 'Computational Psychiatry and the Social Focus of Delusions'

An influential body of research in computational psychiatry draws on models of Bayesian inference and prediction error minimisation to illuminate the formation and maintenance of clinical delusions, especially in schizophrenia. I argue that this work fails to explain an important but often overlooked feature of clinical delusions: namely, that they tend to cluster around a surprisingly small number of themes, the majority of which are social in nature. Drawing on recent social theories of delusions, I explore how Bayesian models - and work in computational psychiatry more broadly - could address this problem. I then extract some more general lessons from this exploration for current debates about the role of experience in delusions and the number of distinct dysfunctions or aberrations that underlie them.

The first workshop of the project will be on delusion formation, featuring six talks from seven researchers in philosophy and psychology:

Carolina Flores (Philosophy, Rutgers)

Clara Humpston (Psychology, Birmingham)

Kengo Miyazono (Philosophy, Hokkaido)

Paul Noordhof (Philosophy, York)

Ema Sullivan-Bissett (Philosophy, Birmingham)

Sam Wilkinson (Philosophy, Exeter)

Dan Williams (Philosophy, Cambridge)

See below for the Programme and titles and abstracts. The workshop is free, open to all, and will take place over Zoom. For updates follow us on twitter @del_by_ex

To register email Ema: [email protected]

Programme

12th July

10:45-12:00: Kengo Miyazono: ‘Salience and Affordance in Schizophrenia’

12:00-13:00: Break

13:00-14:15: Sam Wilkinson: ‘Agent Representations as Generative Models: The Case of Delusional Misidentification’

14:15-14:30: Break

14:30-15:45: Carolina Flores: ‘The Intelligibility of Schizophrenia’

13th July

10:45-12:00: Paul Noordhof and Ema Sullivan-Bissett ‘The Everyday Irrationality of Monothematic Delusion’

12:00-13:00: Break

13:00-14:15: Clara Humpston: ‘Isolated by Oneself: Solipsistic Delusions in Schizophrenia’

14:15-14:30: Break

14:30-15:45: Dan Williams: ‘Computational Psychiatry and the Social Focus of Delusions’

Titles and abstracts

Carolina Flores: 'The Intelligibility of Schizophrenia'

People with schizophrenia are often thought to reason in unintelligible ways. For example, how are we to make sense of believing that one’s partner is unfaithful because the fifth-lamppost along on the left is unlit? In this paper, I draw on work on reasoning biases in schizophrenia (especially by Todd Woodward and collaborators) to argue that the reasoning patterns we find in schizophrenia are intelligible at the folk-psychological level. More specifically, I argue that the reasoning patterns characteristic of schizophrenia express an epistemic character—a unified set of epistemic values, preferences, and traits. For this reason, these patterns constitute an epistemic style and can be understood as expressing a distinctive way of being an epistemic agent. I offer an account of how this epistemic style contributes to the formation and maintenance of delusions in schizophrenia. This account suggests that schizophrenia is, at least in some respects, on a continuum with neuro-typical cognition. It entails that we should separate out intelligibility and rationality. And it helps us reframe questions of epistemic assessment in cases of schizophrenia.

Clara Humpston: 'Isolated by Oneself: Solipsistic Delusions in Schizophrenia'

If there is one concept which most individuals hold as absolute truth, it is likely that they, and only they, can access their thoughts, emotions and actions. Indeed, most people would not even question what makes a thought theirs in the first place – unless the person is mad (I refer here to the schizophrenic kind of madness specifically). Nothing seems to signal madness more than the claims that one is not the producer or owner of one’s own thoughts and actions; to most clinicians, it simply has to be a delusion that needs to be corrected with pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions.

I argue that the observations and interventions by the majority of well-meaning theorists and clinicians barely scratch the surface of the schizophrenic experience. It is extremely difficult to offer a deep enough understanding into what it is like to be on the receiving end of external interference coming from nowhere, or to hold the ‘belief’ that one is not the source or owner of thoughts present within one’s mental space. The core of the experience of a schizophrenic disorder in my view lies within this labyrinth of uncertain, paradoxical, unstable and unsustainable ‘in-between’ states of thought, perception and volition that in their totality contribute to what may be termed ‘ontologically impossible’ experiences sometimes leading to solipsistic delusions.

I aim to explain what it means to go through solipsistic delusions, their significance to the understanding of thought and perception, how they might help with the clinician’s differential diagnosis, before engaging in further discussion on ‘what if’ these experiences are not impossible after all. What if the unity of selfhood and its perceived links to first-personal givenness are nothing more than a historical or social trend? What implications will it have for the constitutive relationship between thinking and the existence of self that is taken for granted? My hope is that by contemplating such questions, theorists and clinicians alike will begin to grasp what it is like to be in the grip of the perplexity and paradoxicality intrinsically associated with schizophrenia, and to appreciate the patients’ realities and truths.

Kengo Miyazono: 'Salience and Affordance in Schizophrenia'

It is a popular view that delusions are (partly) caused by some altered experience. In schizophrenic delusions, the altered experience has something to do with abnormal “salience” (Kapur 2003). To say that an object X is “salient” is, roughly, to say that X “grabs” attention. My proposal in this paper is that X “grabs” attention if and only if X “affords” attention (McClelland 2020). Altered experience in schizophrenia thus involves some abnormal (mental) affordances. I defend this account of abnormal salience in schizophrenia from a recent objection by Ratcliffe and Broome (forthcoming) that both “salience” and “affordance” are unhelpful notions in understanding altered experiences in schizophrenia.

Paul Noordhof and Ema Sullivan-Bissett: 'The Everyday Irrationality of Monothematic Delusion'

Empiricist accounts of monothematic delusion formation have it that the anomalous experiences often had by subjects with these beliefs are explanatorily relevant to their formation. Many philosophers and psychologists have argued that in addition, there is some special irrationality involved in delusion formation, understood as the manifestation of some cognitive deficit, bias, or performance error. Key to this approach is the fact that not all people with anomalous experiences develop delusions, and so the thought goes that we can explain why some subjects develop delusions off the back of anomalous experiences while others do not by appeal to a special irrationality afflicting the former.

We argue that an examination of non-clinical paranormal beliefs shows that it is a mistake to think that monothematic delusional belief usually involves a kind of irrationality distinct from everyday kinds. We turn then to a question which naturally arises from the foregoing, if delusions are not the result of clinical irrationality, what are we to say about their status in this regard? We argue that although delusions are often seen as the most serious form of irrationality, they are in fact, in some ways, closer to the normal case than has been typically thought.

Sam Wilkinson: 'Agent Representations as Generative Models: The Case of Delusional Misidentification'

Social organisms don’t only perceive and reason about inanimate parts of the world; they also perceive and reason about other agents, namely, parts of the world that have in turn their own perspective on the world. What is this cognition (online or offline) of agents and how does it differ from cognition of inanimate parts of the world? My answer here is that agent cognition deploys agent representations, and that these representations are to be thought of as dynamic predictive models (DPM). One area where this account is especially illuminating is in our understanding of delusional misidentification. I end with some general lessons for how we are to think of social cognition more generally.

Dan Williams: 'Computational Psychiatry and the Social Focus of Delusions'

An influential body of research in computational psychiatry draws on models of Bayesian inference and prediction error minimisation to illuminate the formation and maintenance of clinical delusions, especially in schizophrenia. I argue that this work fails to explain an important but often overlooked feature of clinical delusions: namely, that they tend to cluster around a surprisingly small number of themes, the majority of which are social in nature. Drawing on recent social theories of delusions, I explore how Bayesian models - and work in computational psychiatry more broadly - could address this problem. I then extract some more general lessons from this exploration for current debates about the role of experience in delusions and the number of distinct dysfunctions or aberrations that underlie them.